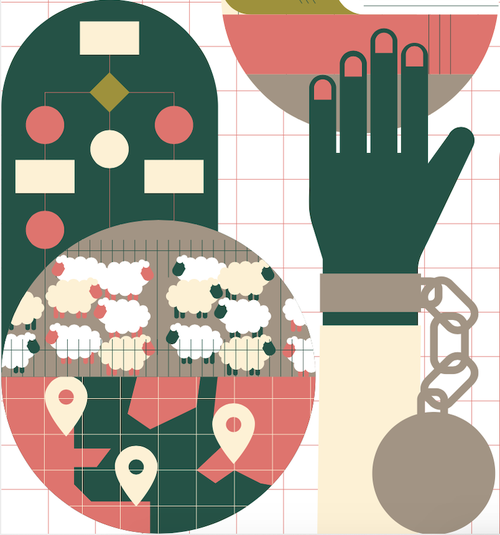

This practice is not new. For over seven centuries, the legal practice of enclosure reassigned common resources (such as pastures and forests) to a single owner. In the 18th century, this was further justified with the coining of ‘the tragedy of the commons’ – the notion that isolated, autonomous individuals will always deplete the commons, and privatisation is the only way to prevent that inevitability. Elinor Ostrom disproved this idea and won the Nobel prize by showing how communities are able to collectively and sustainably manage resources.

In her book Understanding Knowledge as a Commons, she laid the groundwork for also thinking about digital knowledge as a commons – that is, the digital artifacts in libraries, wikis, maps, open-source code, scientific articles, and everything in between. One of the key tenets of Ostrom’s Nobel-winning framework is that the managers of a resource are able to make decisions free from interference from outside authorities. In other words, third parties and outside authorities need to respect the rights of those who manage the commons. This is simply not possible today, as users don’t have the legal right to own data that they generate on platforms.

To manage the web as a commons, we need to make progress on new legal frameworks that respect users’ intellectual property rights. Technologists also need new architectures that encode the values of cooperation and access into the data and code. Thankfully, these technical infrastructures are not only possible, they’ve been around for a long time. A growing number of technologists are challenging the consolidation of power over information systems by creating decentralised protocols and applications. Where government and corporate control are causing harm, decentralised technologies could bring about resilience, self-determination and long-term access.