There is no avoiding the fact that getting a heat pump is expensive. A typical air-source heat pump installation costs between £8,000 and £16,500. With the £7,500 Boiler Upgrade Scheme (BUS) grant which is available to everyone, homeowners still need to pay on average £4,500 upfront. In comparison, a gas boiler replacement would cost the same household around £3,000.

Heat pumps are much more energy-efficient than gas boilers, so they should be cheaper to run. In theory, lower running costs would help offset the higher upfront price over time. But because electricity is expensive – partly due to levies that jack up the price – households don’t see the benefit of that efficiency.

Gas remains relatively cheap in comparison, which further incentivises consumers to stick with gas. This comparison is captured by the electricity-to-gas price ratio, which is at 3.9, higher than most other European countries. Given that heat pumps use about 3.5 times less energy than boilers, the ratio needs to fall below 3.6 for them to become cheaper to run. The threshold is closer to 4 if households disconnect from the gas grid entirely and avoid paying the gas standing charge.

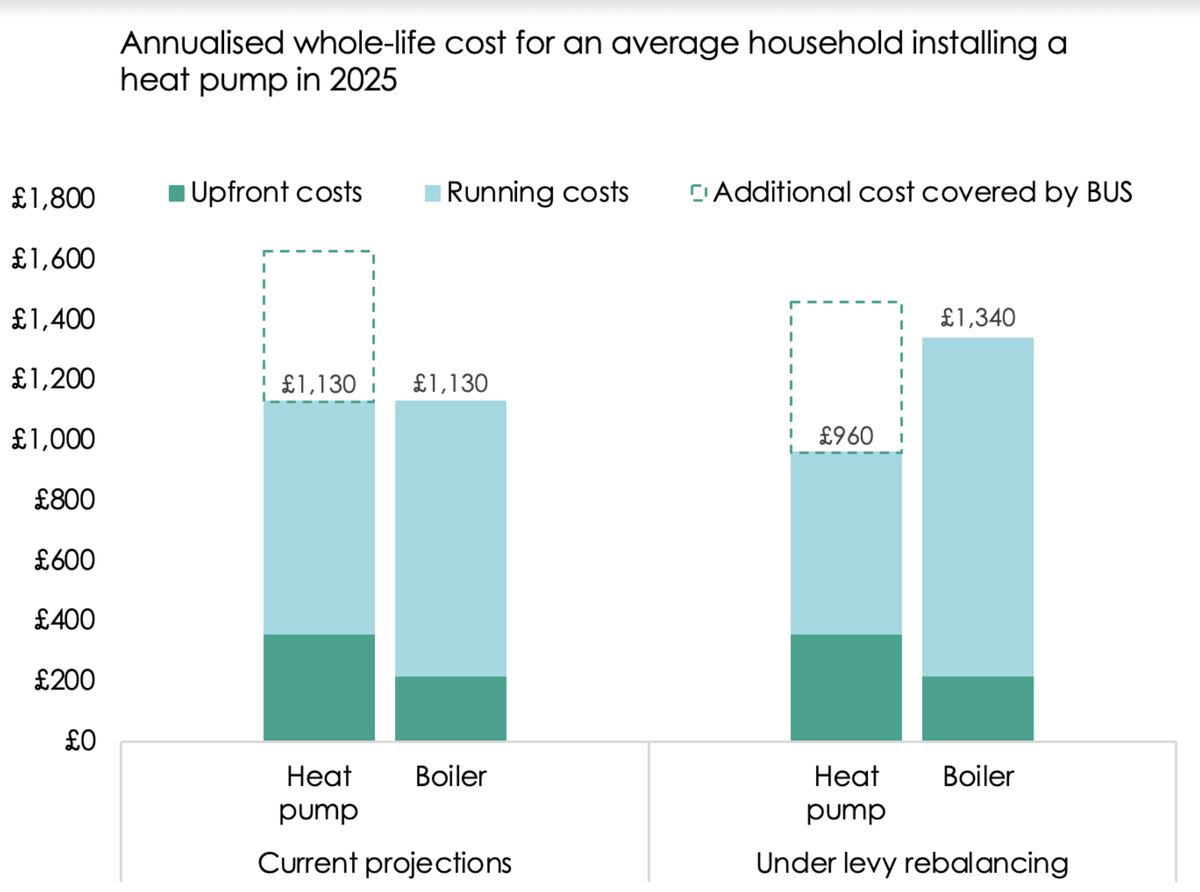

So with upfront costs higher (even after a subsidy) and energy costs slightly lower, the average household installing a heat pump in 2025 can expect to break even with a gas boiler over its lifetime. The total whole-life costs include upfront costs plus any interest paid over time, energy costs and maintenance. The chart below shows the cost comparison annualised for an average home. There will be variation, with larger homes (which would often be suitable for a heat pump) losing out on the switch due to high heating demand.

Comparison of annualised whole-life costs for heat pumps vs. boilers in 2025 for an average UK household

Cost savings clearly don’t offer a strong enough incentive: only around 4% of households who needed to replace their boiler in 2024 chose a heat pump. The Climate Change Committee recommendations state that one in four households need to get a heat pump over the next 10 years. Low-carbon heat is also the only way to stop our reliance on foreign gas with volatile prices. The government needs to act now to make electric heating a much more financially attractive option for the long term.

There is a straightforward way to make electricity much cheaper. Electricity bills are currently artificially inflated by levies collected to pay for legacy renewable energy schemes and energy efficiency upgrades. These could either be shifted to gas bills or covered through public spending.

Moving levies off electricity bills and onto general taxation would reduce the consumer price of electricity by 25%, bringing the price ratio down to around 3.1. A revenue-neutral reform that moves levies to gas bills would not incur any additional public costs. It would instead spread the burden of levies more fairly across households, moving the price ratio even lower to between 2.7 and 2.4. The reform is not without its challenges and will need to be accompanied by targeted energy discounts to protect low-income households on gas from increases in their bills. Nesta analysis suggests that £950 million a year would be enough to cover this.

Rebalancing levies would send a clear signal in favour of electrification. Running a heat pump would then become on average £400 a year cheaper than burning gas.

So what does that mean for whole-life costs? A heat pump installed in 2025 would save an average household £380 per year over the course of its lifetime compared to a gas boiler. This holds even if households take out loans at a 5% interest rate to cover upfront costs (Octopus currently offers APRs around 10%):

Annualised whole-life costs for heat pumps vs. boilers in 2025, with and without levy rebalancing

Over time, energy prices are likely to fall further thanks to more renewable electricity. Heat pump prices may also drop as the market matures, but these reductions are likely to be on the small side. As these ‘natural’ savings accumulate, the need for public subsidy shrinks. BUS is currently scheduled to run until the end of 2027. After that, the government should gradually scale it down to a level that still ensures lifetime cost parity between heat pumps and boilers.

Nesta analysis shows that if levies are moved to gas, then by 2030 a subsidy as small as £2,000 could be enough to make heat pumps cost-competitive on a whole-life basis, assuming households finance upfront costs with loans. Our 2024 report How to make heat pumps more affordable describes three potential routes to affordability, with different levels of government subsidy. All three include a degree of rebalancing levies.

By contrast, what can we expect if there is no progress on policy? By 2030, the price ratio could drop even with no change to levies, but how much will largely depend on wholesale fossil fuel prices which are hard to predict (see second chart below). Either way, levies play a major role. To make heat pumps a financially attractive option, the government would need to keep offering at least £6,000 towards each heat pump in 2030, a level close to current BUS.

This level of public subsidy would be very expensive. The Seventh Carbon Budget advises that 440,000 heat pumps need to be installed in existing homes in 2030. If each of these installations required a £6,000 grant, the government would face a bill of £2.65 billion in 2030 alone, rising even further in the years after. By comparison, the levy rebalancing scenario could bring the cost down to just £880 million in 2030. That’s a difference of £1.8 billion per year. Over the course of the next parliament, maintaining high subsidies could cost an extra £13.8 billion, or £2.8 billion a year on average.

To put this in perspective, BUS spending was around £170 million in 2024. The Feed-in-Tariff scheme which rewards solar electricity generation in homes cost £690 million.

So the government is faced with a choice:

Each year that the price ratio stays high means bigger costs later on, as the heat pump uptake that is urgently needed gets pushed further into the 2030s, let alone the cost of higher emissions.

Failing to reform levies also makes it harder to tackle fuel poverty through clean heat. If electric heating does not guarantee savings, insulation and even gas boiler replacements are prioritised as a safer way to bring down bills for low-income households. These may reduce bills in the short term but are less sustainable and keep the UK dependent on imported gas.

To further bring clarity to the transition, the government should set a date after which no fossil fuel boilers can be installed. This needs to be 2035 at the latest, but could be set even earlier (a 2035 phase-out date was previously announced but then scrapped by the previous government). But without action on levies, a phase-out date will be politically and practically unfeasible. It would be very difficult to justify banning new boilers unless the electric alternative delivers substantial savings to most households. Fixing electricity prices will allow for an alignment between incentives and regulation, too.

Levy rebalancing is the most critical thing the UK can do to shift the dial towards affordable heat pumps. But beyond it, there are plenty of other ways to increase the savings heat pumps bring. Time-of-use tariffs can offer greater savings on electricity, especially if heat pumps are used flexibly, to avoid peaks in electricity demand. Low-interest loans mean people don’t have to pay upfront for a heat pump, and don’t pay too much in finance costs. Raising the efficiency of heat pumps can reduce electricity demand and bring down costs. But none of these changes will make a big enough difference on their own: we need to fix our unfair electricity pricing.

It is difficult to foresee how much exactly lower relative costs will drive heat pump installations, but a survey by Nesta suggests that rebalancing could increase uptake by up to 60%. That would mean we would hit and exceed targets modelled by the Carbon Budget, which we are currently not on track to meet.

Making electricity cheaper isn’t just good climate policy – it’s good value for money. Rebalancing levies would reduce the need for public subsidies, make heat pumps more attractive to households, and support a fairer, faster transition.