We explain our approach to design in Nesta’s Innovation Skills team and how we believe it can help in the public sector.

As Nesta’s Innovation Skills team, our job is to demystify and spread innovation methods, tools and skills. Design is one of the key methods that we help people to become better at.

Over the years, we've noticed that the concept of design is surrounded by quite a lot of confusion and misunderstanding. Therefore, in this post, we would like to clarify what we in the team mean by 'design'.

We are well aware that many have tried before to explain and define design, so this is not meant to be 'just another explanation'. Instead, it’s a way of presenting design that we have found useful to explain its value and what we believe are its key principles.

To begin, what comes to mind when you think of design? For many people, the word conjures up thoughts of creativity, products, architecture, graphics, the aesthetics of something. These are all valid responses, and what we might class as traditional forms of design. But today, the practice of design extends beyond these to encompass broader techniques, and when we talk about design in the field of innovation our focus is more on what we might call ‘strategic design’ or ‘design thinking’.

As the diagram below illustrates, design can function at multiple levels and in different ways. Design professor, Richard Buchanan, captured his thinking into these ‘four orders of design’, illustrating how design as a discipline has moved from the traditional concept of the visual or tangible artefact through to orchestrating interactions and experiences, and to transforming systems.

Buchanan’s model demonstrates the scope and role design can play. It also highlights how we are naturally drawn to the first two orders - graphic design and product design - when asked to consider what design is. Over the past couple of decades, design as a profession, however, has been shifting into the other stages where design takes on a more strategic function as complexity increases.

Designing a symbol or a logo is relatively simple, but designing for systems is much more complex and multifaceted. It involves many actors, often with varying or conflicting interests or objectives, and is concerned with situations that might change over time. Design thinking, in that sense, often refers to the mindset and skills needed for the latter two orders – interactions and systems.

The tricky thing about defining what design means is that, by its very nature, design exists on many levels. It is therefore hard to give one concrete definition.

"There is no single way of looking at design that captures the 'essence' without missing some other salient aspect." Bryan Lawson and Kees Dorst, Design Expertise

Instead, there are multiple lenses that we can look at design through in order to understand it. Design as a method; a process; a product; a problem-solving approach; a form of creativity; a capability. Design can be seen as all of these and more. It is for this reason that we find it difficult to define as a concept, not least because we all see it from different contextual standpoints.

It is also worth remembering that, although humankind has in fact been designing since it began inventing and using tools thousands of years ago, design as a discipline is relatively young when compared to, say, science or the arts. Both of these have a history stretching back many centuries, and are established disciplines with their own body of knowledge and methodologies.

Looking to design, Bauhaus launched one of the first design courses around 1920 - but design as a field of investigation, and a discipline to be advanced, only really began to emerge in the 1960s with the design methodology movement. However, the way those early design theorists talked about design still holds today.

One of the most cited definitions of design comes from a Nobel laureate and academic:

"Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones." Herbert Simon in 1969

Breaking down this definition, there are a couple of crucial factors. Firstly, “everybody designs”. Designing isn’t just for professionals, it is a fundamental human activity and capability. There is, of course, a difference in the more explicit design methods that professional designers use, compared to non-professionals. Everyday design is more implicit, and we might not be aware we are doing it – for example, if you rearrange the furniture in your living room you are actually designing. But throughout our day-to-day lives there are many actions we take that could be classed as designing.

The second factor is around “changing existing situations into preferred ones”. Design is about change, and change can be good or bad. But the importance here is that design should be about improving situations – particularly the human condition – as design should be about making things better, not worse. The aim is to create a preferred situation, a future state, that is better than the current state.

Design: current and future state

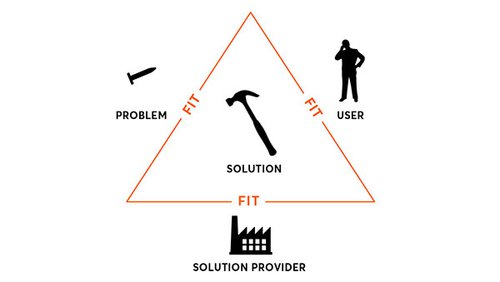

When we talk about design in the field of innovation, our focus is on designing solutions for – and often with – others to achieve that desired future state (i.e. strategic objective). The concept of “fit” is key in this process. Design is ultimately about generating a fit across a number of different elements, as illustrated in the diagram below:

This diagram is, of course, a simplified representation, and it doesn’t take into account the complexity that surrounds these elements in reality. But it is still useful for understanding the key relations around the concept of “fit”. These are:

Solution-problem fit: The solution should provide the right fit for the problem. For example, if the problem is how to drive a nail into a wall, then a hammer offers a good solution, or ‘fit’. But if we want to put a screw into the wall, it’s a less appropriate tool. In that case, a screwdriver would offer a better fit.

Solution-user fit: The solution should fit with the user's physical and cognitive capabilities, preferences and needs. For example, a trained craftsman who regularly uses carpentry tools is likely to have different requirements to a layman who may only use them occasionally.

Solution-provider fit: The solution should fit with those who are going to provide it, the solution provider(s). A solution that has a perfect fit with the problem and end user, but that is costly to create or complicated to deliver, is unlikely to be sustainable.

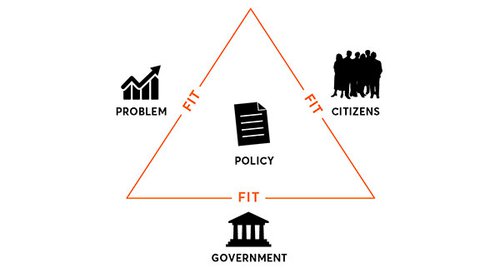

This idea of ‘fit’ can also be expanded to other areas that involve design activity, such as policymaking. Take for example the problem of growing childhood obesity. A government might tax sugar-sweetened drinks as a policy intervention to tackle this issue. But how does this fit with the motivations and everyday routines of children? Will it change their behaviour? And how does it fit with government processes? How will this policy be enforced, and what departments will need to collaborate on it? How much manpower will it take?

Bear in mind that design doesn’t try to create a perfect fit across all three dimensions; rather it aims to create a fit that’s good enough. In order to do that, there are four principles that help generate this fit and that everybody can learn and use:

Empathising: One of the core principles of design is empathy; that by putting yourself in the shoes of your users and learning as much about them as you can, you are more likely to create solutions that hit the mark for them. Often the person doing the designing isn’t the ultimate end user of that product or service. This can create a distance between those experiencing the problems and those coming up with the solutions. So a policymaker might create a new solution to improve the situation of a citizen, and it will then be interpreted and implemented by somebody else. But if the policymaker and service implementor don’t have a clear understanding of the citizen’s context, ambitions and environment in the first place, then there is a high risk that the solution won’t actually be a good fit for the citizen’s lived experience.

Iterating: Assessing whether a solution is good enough to address the problem, should be tested through a trial and error process. This is the essence of prototyping. By building prototypes, any assumptions on what might work are tested at an early stage, and this often leads to a revised definition of the problem or an improvement in the design of the solution. Through this process of going back and forth between the problem and solution, a better fit is created.

Collaborating: Particularly in emerging design disciplines such as social design and service design, design catalyses change by bringing people together and enabling collaboration. Professional designers can often help play a coordinating role here by bringing internal and external stakeholders together. They support collaboration by creating a shared language around design and by developing a common understanding about the user, problem and what the solution might look like.

Visualising: Through visualisation, complex information can be made comprehensible to support decision-making. Visual thinking is the universal language of design and helps to drive experimentation, build common ground across stakeholders and share user insights. Visualisation techniques are used to sketch out ideas, to build prototypes and to discuss and evaluate concepts with stakeholders and end-users. Presenting user data in a compelling, visual way also helps to build empathy (e.g. through tools such as personas or user journey maps).

As we’ve seen throughout this article, design has multiple facets and operates at different levels - from the tangible to the systemic - but they all aim to transform an existing and problematic situation into a preferred one. And by using the design principles above, everybody has the ability to start bringing design approaches into their work and developing solutions that have a better fit with the problem, the end-user the solution provider.

By getting closer to your end users, improving ideas by testing them, bringing together different stakeholders to collaborate, and making things tangible and visible, you can begin to experience the value that design brings.

If you're keen to find out more about putting design into practice, take a look at our guide on Designing for Public Services, or the many tools and resources we've created for the Design for Europe website.